How Clarks Became the Baddest Shoes in Jamaica

To celebrate the of the Clarks Originals Desert Trek, we're revisiting how the iconic Somerset label became the baddest brand in Jamaica.

Loved by rudeboys, treated with suspicion by the constabulary, and waxed lyrical by dancehall DJs, are a certifiable cultural artifact in Jamaica. Despite a ban on foreign-made shoes throughout much of the 1970s, clandestine trade routes between Somerset and Kingston maintained the brand’s unassailable prestige. Al ‘Fingers’ Newman, author of the incredible Clarks in Jamaica book, explains how they became the baddest shoes in the Caribbean.

As told to Gabriel Filippa.

There’s always been a steady flow of music, fashion and culture back and forth between the UK and Jamaica, mainly due to the colonial links between the two countries and the many Jamaicans that settled in the UK after WWII. Jamaican people loved British-made goods, which are traditionally associated with quality and prestige, and Clarks shoes are particularly revered on the island. Clarks targeted Jamaica as an export market as far back as the 1940s when advertisements in local papers like The Gleaner did a lot to establish the Clarks name.

Of all the Clarks models, the Desert Boot is generally regarded as the top style by Jamaicans – especially rudeboys. Some say rudeboys favoured the Desert Boot because it allowed them to be totally silent when creeping up on someone to rob them!

Another well-known Clarks-related story many Jamaicans seem to know is about Joe Williams, a Kingston police officer who was active from the 1960s until the 1980s.

A so-called ‘bad man police’, Joe would go in guns blazing. The story goes that he once raided a Coxsone Dodd dance where King Stitt was selecting. He cut off the music and told everyone wearing Clarks booties to get to one side of the dance and everyone not wearing Clarks to get to the other. That was his way of rounding up the rudeboys because he knew they’d all be wearing Clarks. Apparently, people were removing their Clarks and dashing them away to avoid being arrested. Many people in Jamaica told me they were beaten up by police just for wearing Clarks. ‘You must be a criminal,’ the police would say, ‘How else could you afford to wear those Clarks?’

Rudeboys are known for their style and fashion. They also love Desert Boots in a big way, though, to be fair, any shoe that says the word Clarks on it is a hit in Jamaica. The Desert Boot is a great-looking shoe, and the quality, especially pairs made in England at the Clarks Bushacre factory in Weston-super-Mare, is superb. Those UK-made shoes would last for years. There’s a phrase in Jamaica, ‘My Clarks can’t bend!’ meaning ‘My Clarks cannot be destroyed!’ The crepe sole – known in Jamaica as the ‘cheese bottom’ – is another factor. The Desert Boot is so versatile it can be worn with a suit, shorts, workwear or jeans – and it always looks good. Plus, because they were expensive, they were also a status symbol. As Jah Thomas told me, ‘Rudeboys love expensive things!’

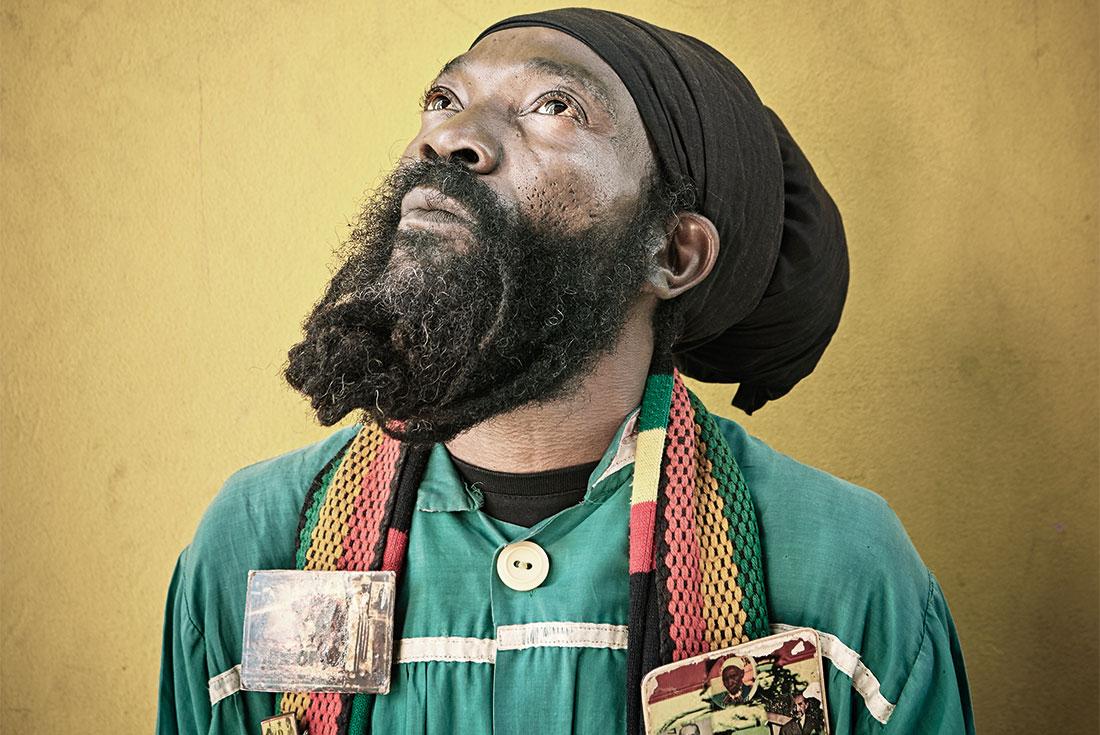

When we met the DJ Jah Stitch, who sadly died last year, he told me that his posse, the Spanglers, popularised the Desert Boot in Jamaica. Always dressed to the nines and never without his Clarks, Stitch operated a sound system on Princess Street in downtown Kingston, where we went to meet him. He told me that the Spanglers set a lot of trends in West Kingston, such as the Arrow shirt and the Mesh Marina (string vest). Like all rudeboys, the Spanglers love Wild West movies. They actually got their name from a villain called Jud Spangler in the 1964 Western The Quick Gun.

The photograph of Jah Stitch looks quite serene, but the photoshoot attracted a lot of interest, and I had to deal with quite a few people behind the scenes while Mark got the image. In the mid-70s, Stitch was shot through the mouth. His face drooped to one side, and he talked with a slur. Afterwards, Stitch came out of hospital and recorded the tune ‘No Dread Can’t Dead’ for Bunny Lee. Apparently it was a miracle he didn’t die. The high murder rate is one of the reasons Clarks sold so well in Jamaica. Since there are funerals almost every week – and you can’t be seen in the same pair of Clarks you wore at previous funerals – rudeboys always had to have a fresh pair.

In the 1970s, Jamaican prime minister Michael Manley banned the import of foreign-made shoes into Jamaica, so Clarks became even scarcer and more expensive. Touring musicians would buy Clarks in the UK and bring them home. They’d sell their music and records and use the money to fill their suitcases with Clarks. Producers like Henry ‘Junjo’ Lawes repatriated dozens of pairs to Jamaica. There is no social welfare system on the island, so many of the poorer neighbourhoods are looked after by local dons. Junjo would go back and distribute Clarks to his community. If you knew someone that was heading to the UK, the best thing they could bring you back was a pair of Clarks.

Some intrepid Jamaicans travelled to the small village of Street in Somerset, southwest England, where Clarks were made. If you really knew what you were doing, you’d visit the stores that sold Clarks seconds, which are shoes with slight imperfections. For Jamaicans that knew about these stores, it was heaven on Earth!

The earliest tune I’ve found that mentions Clarks is from 1976 when Dillinger referenced Clarks in his track ‘CB200’. He talks about riding around on his Honda CB200 motorcycle, buying various bits and pieces, including a pair of Desert Boots or ‘Clarks booties’ as they are known locally. In the mid-80s, dancehall artist Little John had the first big Clarks hit with a song called ‘Clarks Booty’. When that was played in dancehall, people would take off their Clarks and wave them around in the air.

There are hundreds of other Clarks references in Jamaican song lyrics. I have a collection of more than 200 reggae tracks that reference the brand. In 1978, Trinity voiced a tune called ‘Clarks Shoe Skank’. Then Ranking Joe put out ‘Clarks Booty Style’ in 1980, and Scorcher released ‘Put On Me Clarks’ the same year. Then, of course, in 2010, Vybz Kartel released three tunes about Clarks, which provided my inspiration to do the book.

I don’t think any country loves a brand more than Jamaica loves Clarks. It’s not a fashion thing that comes and goes. Clarks are an inextricable part of Jamaican culture that reaches all professions and demographics. Gangsters, police, doctors, politicians, nurses, hustlers, teachers, the young and the old – they all love Clarks with a passion!

Ready to lace history? Clarks Originals are celebrating 50 years of the globe-trotting Desert Trek with a rendition that would make the rude boys proud. To read more about the Desert Trek and cop a pair of your own, head