Making Strides: The Sneakers That Defined Running

As far as sports go, running is a pretty cheap and accessible one to get into. As a natural gait, the concept has been around since we evolved into two-legged beings, but you might be surprised to learn that shoes designed specifically for road running are actually a relatively recent invention. Until the 1960s, the idea of ‘jogging’ was pretty alien. Any racing or training was left strictly to the pros, and anyone else seen picking up the pack was eyed with serious suspicion – even occasionally getting stopped by the police. It wasn’t until a relatively fresh-faced Bill Bowerman (then track coach at the University of Oregon) returned from a trip to New Zealand raving about the benefits of a casual jog that things started to change. After dropping his book Jogging in 1967, Bowerman kicked off a craze that was about to shape the sneaker (and sports) scene forever.

While track and trail running have their own specifics, we have the birth of road running shoes to thank for the technological evolutions that have been instrumental in informing both the sport and the wider sneaker scene. Nylon uppers, EVA soles, BOOST and Nike Air were all born out of the quest to design a better runner. With that in mind, we set out on a mission: to sprint through the shoes that defined the sport of running.

1960s: Track Stars

Running shoes have been around in early track and cross-country forms since the 1800s, but the birth of the modern road running shoe arrived alongside the growing sport of jogging in the 1960s. Up until then, most running shoes had featured spiked soles, either for providing traction on the track or trail terrains.

Initially, the omittance of running spikes came with the New Balance Trackster, which was born at the very start of the 60s. The Trackster swapped spikes for a unique rippled sole unit that managed to maintain the same level of traction. Also arriving in a huge range of widths, the New Balance Trackster was quickly adopted by college athletes all over the USA. Although other modern day track and cross country runners still tend to rely on spikes, the Trackster’s influence can be seen throughout the rest of the running scene, with its wavy sole paving the way for road runners to come. Among those, was the Onitsuka Limber Up, a runner that caught the eye of Nike (then Blue Ribbon Sports) founder Phil Knight, which also featured a wavy textured, traction-heavy sole unit. Knight went on to send a couple of pairs to his track coach at the University of Oregon, Bill Bowerman, and the duo went into business as the exclusive US suppliers in 1966, selling pairs out the back of Knight’s car. Onitsuka’s hot run then continued with the Tiger Marathon, in which Amby Burfoot won the Boston Marathon in 1968.

1968: Cushioned Cortez

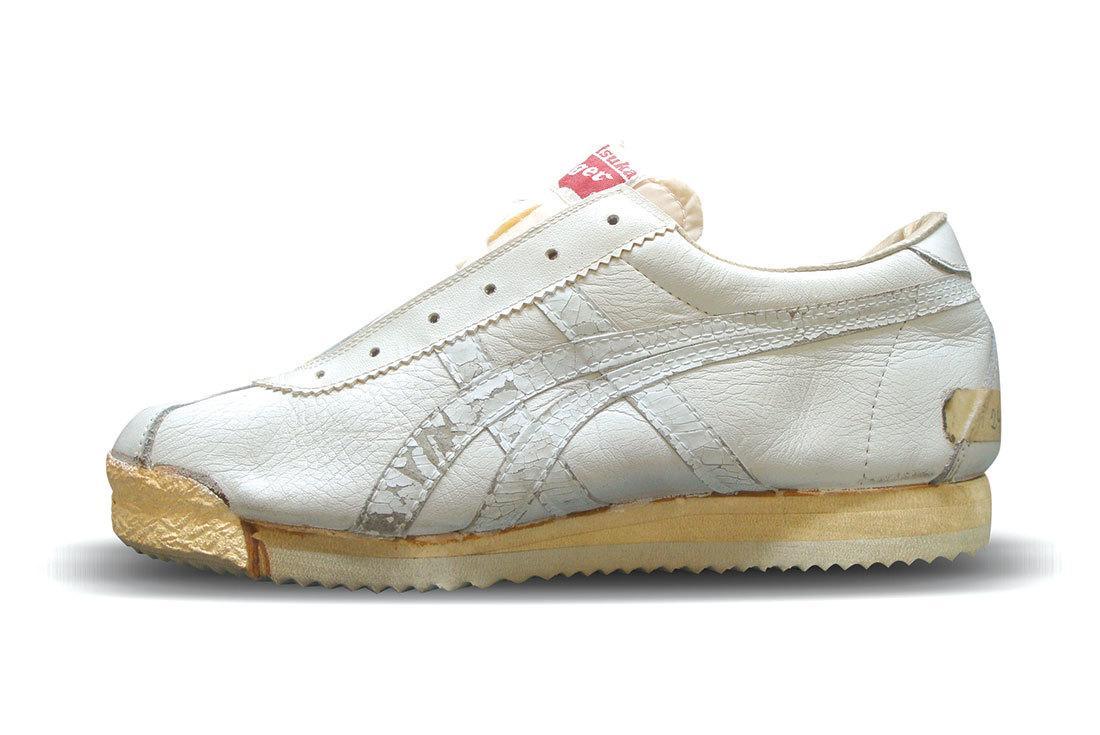

The deal with Onitsuka had come at the perfect time for Blue Ribbon Sports. Bowerman had just released his hugely successful book on jogging, managing to get over a million Americans interested in the sport. Notorious for modifying his Olympic athletes’ sneakers, Bowerman soon pitched a new model to Onitsuka, a combination of the Power Up and Limber Up (wavy sole and all) that he called the Cortez, or Corsair. Alongside the ribbed traction pattern, the shoe also benefitted from a full-length, wedge shaped foam sole unit, adding the benefit of cushioning to the shoe’s arsenal. The model may have resulted in a messy lawsuit later down the line, but there’s no denying that the Cortez’s conception is a key moment in running shoe history.

1970s: Cooking Up a Storm - Nike Waffle

As Nike continued to establish themselves outside of Blue Ribbon Sports, they honed in on the angle Bowerman knew best: running. By this point, joggers had stopped getting funny looks from police, and the sport had become a countrywide phenomenon. Further disregarding the need for studded shoes, brands were taking cues from the Cortez and Trackster and were experimenting with upping the traction on non-studded soles. Bowerman’s solution actually ended up coming to him over breakfast, and thanks to his trusty waffle maker, Nike’s Moon Shoe was born. This was quickly followed by the Oregon Waffle Racer, and soon brands were experimenting with traction-focused, rippled and ridged sole units that would work on the tracks and tarmac. The Oregon Waffle also featured a lightweight nylon upper, a switch from the heavy leather seen on training shoes before it. This was another key change up in the construction of running shoes to follow.

1980s: Running on Air

EVA foam midsoles and moulded rubber outsoles had quickly become standard among 70s running shoes, but the Swoosh’s next invention was about to change the game again. The nerds at Nike had enlisted some help from a former aerospace engineer named Frank Rudy, who’d come to Beaverton in 1977 with the idea of an encapsulated sole unit filled with pressured filled gasses – an air bag, if you will. Knight himself put the prototype through its paces before limited quantities of the Tailwind were released ahead of the 1978 Honolulu marathon. Soon after, the silhouette hit the shelves.

The invention of Air was a revolution within the sneaker space, providing an all-new solution for shock absorption within running. But though Nike may have dominated Air tech (and patented the hell out of the Air bag), they weren’t the only brand to use air as a material. In 1986, Hi-Tec released the Badwater 146, using what they called the Air Ball Concept (ABC). This featured an interchangeable cylinder that compressed on impact, before decompressing to help propel the runner on their stride, essentially rendering it an early development in energy return. Of course, Nike’s rev-air-lution only became more eyecatching with the launch of visible Air in the Air Max 1, which ushered in healthy competition from the likes of ASICS and their GEL line.

1990s: Saucony Race On

Though Saucony was founded in 1898, a few marathon wins in the 1980s saw the US-based brand finally hit their running stride. Then, in 1991, Saucony came correct with the introduction of their Grid Cushioning System (GRID), which was inspired by tennis rackets and saw a system of Hytrel filaments come embedded in an EVA midsole unit that helped to strike the balance between comfy cushioning and supportive stability.

Saucony’s efforts didn’t end there either. The brand helped to push EVA further with the introduction of a dual-density EVA midsole on the Saucony Flight. This combined additional foams for a firmer density and helped to protect runners against overpronation. It pretty much remains industry standard, for new lifestyle sneakers at least.

1995: Zoom, Zoom

While the Air Max franchise was still going strong (read: quickly seeping into the lifestyle market), Nike were continuing to experiment with how they could adjust Air for running. The mid-90s saw the introduction of Zoom Air (then called Tensile Air) in the Air Zoom LWP. The modified Zoom Air unit differentiated itself from normal Nike Air as it was specifically designed to provide more explosive power using smaller Air units, highly pressurised Air and tightly stretched fibres to absorb impact, before bouncing back with extra oomphf. A landmark development in Air’s fairytale, Zoom Air remains a mainstay in Nike’s running offering today.

2000s: Vibram Step Up

Air, GEL and ultra-cushioned foam battled it out throughout the 90s, but as the 2000s rolled around, runners had started to cut right back. Sneakers had become weighed down by gimmicks and bulked up with cushioning, and to make matters worse, there were conflicted studies about the effect of running in ultra-cushioned shoes. Some researchers had even suggested that runners’ feet were stronger without shoes at all – and sure enough, there had even been instances of bare-footed marathon wins. But not everyone was ready to completely ditch their shoes, and so Vibram stepped up to the mark.

Originally known for making soles, Vibram dropped their Five Fingers to whet the appetite of the barefoot-curious. Half sock, half glove, the style had been marketed as a water shoe thanks to its grippy sole and individual toes, but that changed when the then-president of Vibram decided to take them on a run. Having struggled with knee pain wearing other shoes, he was convinced that the Five Fingers brought him no pain at all, and began to claim that they could help to prevent injury in runners. However, the minimalism trend didn’t last long… minimalist shoes were still resulting in injured runners, and Vibram, in particular, were sued for false advertising.

2013: Running Gets a Boost

Even as EVA evolved into Phylon, foam-soled running shoes all eventually ran into the same problem: they couldn’t keep their bounce forever. In 2013, adidas introduced the world to a new option: the Energy BOOST. The sole was formed with a bespoke new form of TPU that came in a block-copolymer structure for a springy feel. The sole was made up of hundreds of these pellets, each of them retaining their own shape even when squished, which would give the sole a much more reactive feel underfoot than a simple slab of foam ever could.

adidas took full advantage of the revolutionary new running tech, slapping a BOOST sole on a ton of its lifestyle models as customers raved about how comfortable it was. But the running world moves quickly, and in running tech terms, BOOST never evolved enough. Especially when you consider the breakthrough that came next…

2016: Breaking the Records, and the Rules

The Swoosh shook up the running world once again with the birth of the Nike Zoom Vaporfly 4% (so named after the amount Nike believed it could improve marathon speeds by) in 2016, which kickstarted the modern-day super shoe era. Engineered in the Beaverton labs, the shoe’s construction consisted of Nike’s Zoom X foam designed to increase energy return, a carbon fibre plate for enhanced propulsion, and a super-lightweight Flyknit upper. None of these elements were new, but what was different was how the carbon plate had been embedded into the foam. That year, the top three finishers in the Rio Olympics Men’s Marathon wore the Vaporfly. The shoe was also worn by Eliud Kipchoge for Nike’s initial sub-two hour marathon attempt, Breaking2, where the runner finished in a time of 2 hours and 25 seconds. Naturally, the shoe progressed into the Nike Zoom Vaporfly NEXT %. At this point, Nike had their highest market shoe ever within the running world. An estimated 95 of the first 100 finishers in the 2018 Valencia Marathon were wearing Vaporfly shoes, and quite frankly, the shoes were breaking records and setting fastest times left, right and centre. Things peaked when Kipchoge finally broke the two-hour barrier wearing a prototype of the Nike Alphafly, another evolution of the line. Due to certain factors this couldn’t count as a World Record – but that’s held by the late Kelvin Kiptum, who set a time of 2 hours and 35 seconds in the Nike Alphafly 3.

The Vaporfly series was so competitive that World Athletics had to step in to determine the legality of the running shoes. Previously, the rules had stated that ‘shoes must not be constructed so as to give athletes any unfair assistance or advantage – and any type of shoe used must be reasonably available to all in the spirit of the universality of athletics’, but due to the ambiguity of the language, it was barely enforced. The rules were eventually settled in 2020, where the new rules confirmed that from April 30, any shoe must have been available for purchase for four months before it can be used in competitions and that prototypes could not be used during races. They also ruled out a version of the Alphafly, introducing new legislation that ruled out any shoes with soles thicker than 40 millimetres or more than one piece of carbon fibre (or other rigid material) in the form of a plate. Later that year, the rules changed again. Prototype shoes were once again able to be used in competition, providing they met the other technical specifications and were only subject to a 12-month development period. However, prototypes still can’t be worn for the World Athletic Series or Olympic Games.

2023: The Era of the Super Shoe

After the birth of the Vaporfly, Nike had been described as being two years ahead of everybody else. But in 2023, other brands had done more than just catch up. Moving on from BOOST, adidas had chosen to focus their efforts on their Adizero series, and with that came the adidas Adios Pro Evo 1. Weighing 40 grams lighter than the adidas Pro 3, it comes with a Lightstrike Pro midsole which (you guessed it) houses a carbon fibre plate.

The Adios’s arrival was announced a week before the Berlin Marathon, where Tigst Assefa laced up a pair and shattered the existing women’s world record, coming home in a time of 2:11:53. Then, Sisay Lemma cruised to victory in Boston, logging a time of 2:06:17. The shoe also dominated at this year’s London Marathon, taking home a win and multiple podium finishes. But even though the running world welcomed the competition, the adidas Adios Pro Evo 1 was shrouded in a controversy of its own. While the newest iteration of the Alphafly will set you back $285 and see you through 250 miles, the adios Pro Evo 1 retails at a cool $500 and is described as a one-race-tool. That’s right – for $500 you can get yourself a shoe that lasts for 26.2 miles, plus breaking-in time.

Given that it took so long to catch up with the Vaporfly, you’d be forgiven for thinking that running tech has hit its peak. But the boffins in Beaverton, Bavaria and beyond are always experimenting. Over in Switzerland, On have just debuted a new form of spray tech that’ll eventually allow them to produce custom elite racing shoes on a huge scale. New Balance are pressing forward with FuelCell, and though Saucony’s stake is small, the brand has a solid runner in the Endorphin Elite. HOKA, known primarily for their ultra-cushioned soles, have worked Peba foam and a carbon fibre plate into their Cielo X1, bringing a Metarocker feel to the super shoe market. The reality is that progress never really stops, and though these pairs have defined running until now, it’s only a matter of time before another shoe changes the course of the sport once more.